Civil War

Thomas Hunt Morgan, Columbia University (1922)

Edited by Sydney Fair (2021)

Thomas Hunt Morgan (1866, 1945) was an American scientist from Kentucky. Morgan made many contributions to the study and research of genetics. While Gregor Mendel (1822, 1884) is often assumed to be the “father of genetics,” Morgan made equally important contributions to the field. Morgan, in particular, is known for his experiments involving fruit flies (drosophila). He was able to take genetics a step further, as no one had done before. Morgan's most important work occurred during the first few decades of the twentieth century. His main interest was understanding the mechanism for how traits were passed down from parents to offspring It is important to remember at this time, the precise operations of genetics were still poorly understood. Many scientists and non-scientists still assumed the Lamarckian view that people inherited certain characteristics based on the race, age, gender, religion, behavior, or culture of their parents.

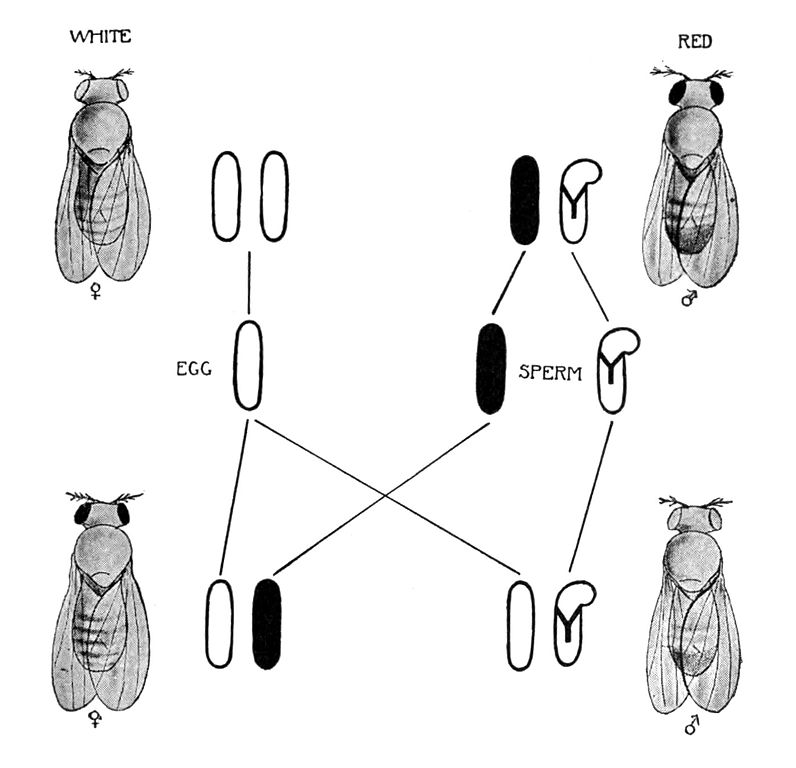

In 1910, for first time Thomas Hunt Morgan realized the genetic origin of eye differences among the drosophilae. The flies normally had red eyes, but he noticed a few of the flies had white eyes. He asked how the traits were inherited in this way. Morgan and his students conducted experiments in his fly lab at Columbia University. Because of the drosophila's short reproductive cycle, they were able to breed numerous generations of the flies and observe their genetic outcomes. After doing an analysis of the flies, they were able to confirm what is known as chromosome theory. In short, the chromosome theory holds that genes are found in certain places on chromosomes, which are molecules that pass genetic information from parent to offspring. Below is the excerpt from Morgan's book Some Possible Bearings of Genetics on Pathology. Written in 1922 when Morgan was a professor of zoology at Columbia University, this book contains a synthesis of Morgan's most important conclusions about genetics from the research done in his lab during the preceding decades.

When the drosophila was crossed to the normal version, the mutant aspect disappeared in the hybrid. If a hybrid is bred to produce all normal offspring, then half of the drosophila will carry the gene. Even though these flies were crossed, the result will only still have a normal outcome. A normal outcome is one without the mutant gene present. When the heterozygous flies breed, 25% of them will have vestigial wings. Vestigial wings are genetically altered and or modified, and it results in them being crumpled up. When the wings are in this state, they cannot obviously be used. At this point, it is unknown which recessive genes are widespread in the human genome. However, in the present day, scientists are well aware of the genes within the human genome. Individuals who have the mutant genes, appear to be part of certain communities. Individuals who have this similar gene seem to have come together. However, when some individuals are absent from these communities, the genes have the ability to not be passed on to the next generations.

My illustration may give, however, an entirely erroneous idea as to chance of a recessive character contaminating the race. If one can control the mating's, so that outbreeding takes place each time, the result would undoubtedly be like that in our diagram; but what chance is there for a recessive character, that is neither beneficial or nor injurious, if left to itself, to contaminate widely the race with its gene? The answer is that for any one defect there is hardly any chance at all. On the other hand, there is always a possibility that a defect may become widespread despite the chances in each turn. If a recessive character is selected against each time it appears on the surface, the chance is extraordinarily small that the gene for such a character could ever become widespread in a race. If the recessive character is advantageous, its chance is somewhat better, but still the chance that it may be lost is very great.

Let us turn for a moment to the inheritance of a mendelian dominant character, and to simplify the situation let us first assume that the character itself is neither advantageous nor disadvantageous. It is popularly supposed that if a trait is dominant, it will be expected to spread more widely in the race than will a recessive character. This is owing largely to a verbal confusion. Colloquially we thing of dominance as meaning spreading. A dominant nation, for example, is one that is spread widely over the face of the earth. But a mendelian dominant should carry no such implications. A dominant gene, if crossed into a race, will stand the same chances of being lost as a recessive gene.

The situation is similar in many ways to the inheritance of surnames in any human population. A new surname introduced is likely to disappear after many generations. There is a bae chance, however, that it may be spread. Of course, if a dominant character is advantageous in itself, it will have a better chance of spreading through the race, than will an advantageous recessive character, because every hybrid that carries one dominant gene shows also the character, which increases the chance that it will propagate and spread the genes. But, on the other hand, if a dominant character is injurious, it will have a smaller chance if spreading that will an injurious recessive character; for, the recessive may be carried by the hybrid without showing itself, and therefor will not place the hybrid individual at a disadvantage.

In connection with the question of spreading of mutant genes in the race, there is another consideration, seldom referred to, that may occasionally have some weight in accounting for the dispersal of genes. In some combinations the hybrid may be more vigorous and more fertile than either parental race. Hence it may have a better chance of survival than an individual of either parental stock. It is a difficult question, that we cannot answer at present, whether a mixed strain has a better change at survival than one or another of the strains of which it is made up. The possibility that some hybrid strain may be better than either pure strain is enough to put one on his guard against the popular doctrine of racial purity so-called. Whatever advantages some kinds of pure races mankind may have, from a political, religious, or militaristic viewpoint, this should not blind us to the possibility of the biological advantages that certain mixtures may bring about. I emphasize the statement that certain mixtures of races may have a biological advantage. It is equally possible that other combinations may have a biological disadvantage. We are far from being able to state at present what combinations are beneficial and what are biologically injurious. It is an interesting problem, one of deep significance I think for the future of the human race, but mixed up as it is at present with difficult social and political questions it is a problem that only a light hearted amateur or a politician is likely to be dogmatic about.

Morgan, Thomas Hunt. Some Possible Bearings of Genetics on Pathology. Lancaster, Pa.: Press of the New Era Printing Company, 1922.

Allen, Garland E. Thomas Hunt Morgan: The Man and His Science. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Miko, Ilona. “Thomas Hunt Morgan and Sex Linkage.” Nature Education 1, no. 1 (2008): 143. 2008.

Kohler, Robert E. Lords of the Fly: Drosophila Genetics and the Experimental Life. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004.

Kenney, Diana E. and Gary G Borisy. “Thomas Hunt Morgan at the Marine Biological Laboratory: Naturalist and Experimentalist.” Genetics 181, no. 3 (2009): 841-846.

Shine, Ian, and Sylvia Wrobel. Thomas Hunt Morgan: Pioneer of Genetics. 1st ed. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1976.